Learning More:

Cannabis Harm Reduction

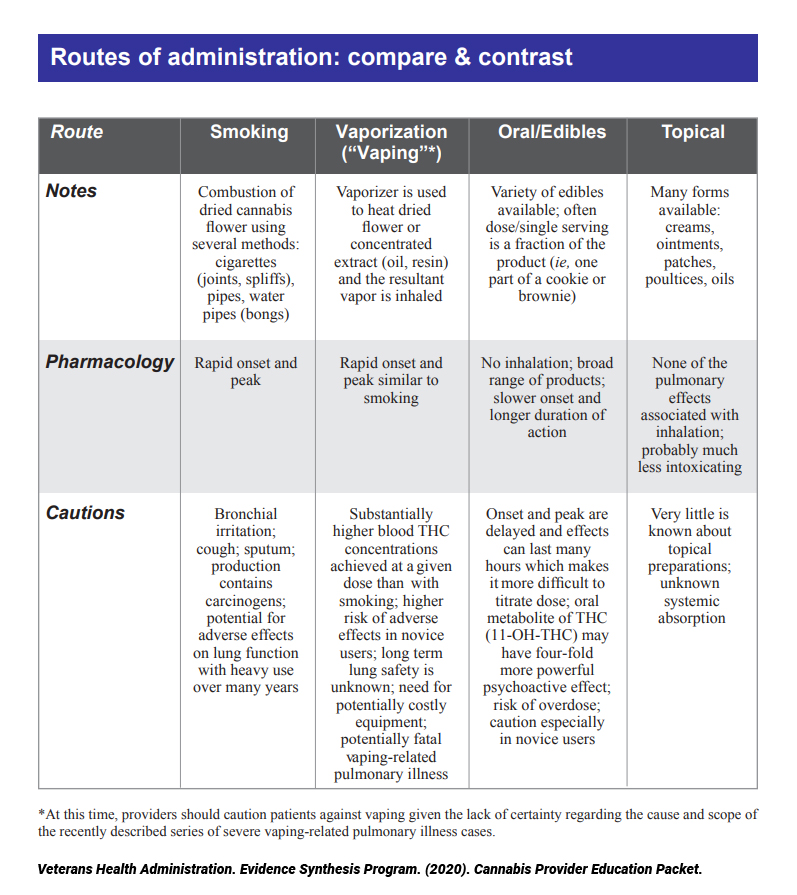

Routes of Administration

THC & CBD

- Cannabis contains cannabinoids, including THC (psychoactive) and CBD (non-psychoactive), which affect the body and mind differently. 1

- THC is the primary psychoactive component of cannabis, working primarily as a weak partial agonist on CB1 and CB2 receptors with well-known effects on pain, appetite, digestion, emotions and thought processes mediated through the endocannabinoid system, a homeostatic regulator of myriad physiological functions, found in all chordates. 12

- THC can cause psychoactive adverse events depending on dose and patient’s previous tolerance. Its use is applicable for many symptoms and conditions including; pain, nausea, spasticity/spasms, appetite stimulation, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), insomnia et al. 12

- CBD is non-intoxicating, and has been shown to help with similar symptoms, with added benefit as an anticonvulsant, anti-psychotic, neuroprotectant, and anti-inflammatory (including autoimmune conditions). 12

- CBD is also a key component in medical cannabis and cannabinoid products used alone or in combination with THC for various medical conditions, such as epilepsy and chronic pain. 35, 36

- A consensus-based task force recommendation for treating chronic pain with medical cannabis based their treatment approaches on CBD doses, not THC Studies also suggest that CBD modulates the side-effect profile of THC. 35, 36

- High THC content in cannabis has been identified as a risk factor for acute and chronic adverse outcomes, including mental health problems and dependence. 37

- As THC is the principal constituent responsible for the psychoactive effects of cannabis, it is the optimal standard unit to measure, especially with regards to safety.38

Learn about drug interactions and cannabis

Smoking Facts

- Smoking is the most common method of consuming cannabis. 39

- The average amount of cannabis smoked per day in Canada, is 1.3g. 39

- Common joint sizes include: 1g (1000mg), ½g (500 mg), and 1/4g (250mg). 39

- On average, joints sold at Cannabis NB have a THC content ranging from 10% to 30% . 39

- Dried cannabis has a natural biological maximum of 30% THC (300 mg/g). 39

Vaping Facts

- Vaping cannabis results in 20-80% higher THC concentrations in the bloodstream compared to smoking it. 31

Edible Facts

- Edible cannabis products are capped at 10 milligrams (mg) of THC per package in the province. 40

- A dose of 2.5 mg (0.025%) of THC is sufficient to produce psychoactive effects for some individuals. 23

- Consume no more than 2.5 mg of THC and wait to feel effects before taking more. 3

Sublingual Oil Facts

- Cannabis NB dispensaries have oral sprays in addition to drops of oil. 3

- Oral sprays come with pre-measured doses, allowing for more precise dosing compared to using droppers. Each spray typically delivers a consistent amount of the cannabis extract, making it easier for users to control and monitor their intake. 3

- It is recommended to consume no more than 2.5 mg of THC or one “activation” (whichever is less) and wait to feel effects before increasing the dosage. 3

- An “activation” is a measurement used when dosing oil and will be different based on each oil’s volumes, composition and potency.41

- The term “activation” refers to a process called decarboxylation wherein tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), is converted into the psychoactive compound, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). For example, if an oral spray says, “Total THC per activation 8 mg”, it means that 8mg of THC will be dispensed per drop or spray. 41

Cannabis & Reproductive Health

Research suggests that using cannabis products during pregnancy can harm both female reproductive systems and early childhood development. Given the currently limited data available on human subjects, it is recommended that patients exercise caution when considering cannabis use during pregnancy due to potential adverse effects on impregnation, fetal growth and development.

Cannabis Usage Among Women

•Cannabis use among women is extremely prevalent among Canadians. 63

•23% of females between ages 16-19: have used cannabis daily or almost daily in the past 12 months

•28% between ages 20-24: have used cannabis daily or almost daily in the past 12 months

•20% of females 25 and older: have used cannabis daily or almost daily in the past 12 months

•After tobacco and alcohol, cannabis is the most commonly abused substance among women of childbearing age. 45, 56

Cannabis and Pregnancy

•Cannabis use can impact female hormones and reproduction, potentially causing anovulatory menstrual cycles due to reduced estrogen and progesterone. For these reasons, individuals trying to get pregnant are advised not to use cannabis, but this does not guarantee use will prevent pregnancy. 8

•THC has been shown to disturb important reproductive events like folliculogenesis and ovulation.48

•In heavy users, it can take up to 30 days after stopping cannabis use for THC levels to be undetectable in the blood, meaning that even if one has stopped using cannabis, THC may still be in the blood and be passed onto the fetus. 50

•Almost half of pregnancies are unplanned, and many women don’t realize they’re pregnant until five weeks gestation, making it difficult for women to know when to abstain from substances to protect the baby. 45

•The disposition of THC has been studied in several animal models including mice, rats, rabbits, dogs and nonhuman primates. Data from the specified preclinical species show that THC readily crosses the placenta, although fetal exposures appear lower than maternal exposures. 51, 58, 55

•THC exposure in utero has shown to significantly decrease fetal folic acid uptake, which is essential for embryo development. Low levels of folic acid in pregnancy are associated with miscarriages, neural tube defects, and low birth weight. 8, 46, 56, 57, 58

•Data suggests that maternal cannabis use during pregnancy impacts children’s neurocognitive functioning, with deficits in memory, verbal, and perceptual skills; impaired performance in oral and quantitative reasoning and short-term memory, impaired executive functioning, and deficits in reading, spelling, and academic achievement. 46, 47, 56, 64

•Not only affecting the fetus neurologically, THC reaches the cellular level, which can interfere with critical pathways for cellular growth and formation of new blood vessels. 56

•Studies have confirmed that in other mammalian species, fetal exposure to THC does not result in changes in long-term physical growth but may negatively impact certain aspects of cognition and heighten the occurrence of behaviors that are consistent with anxiety. 51

•Recent research shows that there can be indirect exposure to cannabis through passive smoking, which is when you involuntarily inhale smoke from another person. 54, 58, 62

•The THC absorbed passively depends on several features related to the condition under which passive inhalation took place, such as environment, duration, and more. 54, 58, 62

Cannabis and Breast Feeding

•Data on the effects of cannabis exposure to the infant through breastfeeding are limited and conflicting. 46

•In heavy users, it can take up to 30 days after stopping cannabis use for THC levels to be undetectable in the blood, meaning that even if one has stopped using cannabis, THC may still be in the blood and be passed onto the fetus. 50

•THC is a lipophilic compound and has been shown to remain in human breast milk for several weeks. 45, 55, 59, 61

•While breastfeeding, there may be up to eight times more THC in breast milk than in a mother’s blood. 50, 55, 59, 61

•Babies exposed to THC through breastmilk may be drowsy, have reduced muscle tone and exhibit poor suckling, which could impact breastfeeding success and the baby’s nutritional status. 50

Cannabis and Infertility in Men

•Cannabis use is a risk factor for poor sperm morphology. 65

•Cannabis use is associated with lower sperm concentration and total sperm count. 52

•Erectile Disfunction is twice as high in cannabis users compared to controls. 60

•THC indirectly decreases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion by the hypothalamus. 48

•THC disturbs important reproductive events like sperm maturation and function. 48

Helpful Links & Resources

- College of Family Physicians of Canada: Guidance in Authorizing Cannabis Products Within Primary Care

- Health Canada. Information for healthcare professionals: cannabis (marihuana, marijuana) and the cannabinoids: dried or fresh plant and oil for administration by ingestion or other means psychoactive agent.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research.

- Veterans Health Administration. Cannabis Provider Education Packet

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction: 7 Things You Need to Know About Edible Cannabis

- Health Canada: Cannabis

- Government of Canada: Legalizing and strictly regulating cannabis

- Government of New Brunswick: Cannabis

- Canadian Medical Association: Cannabis

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health: Cannabis

- Canada’s Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction: Cannabis

Graph: Cannabis Pharmacokinetics

- MacCallum CA, Russo EB. Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2018; 49:12-19. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.004 Published March 2018. Accessed 12 March 2023.

- Lucas CJ, Galettis P, Schneider J. The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. British Pharmacological Society Journals. 2018; 84(11): 2477-2482. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13710 Published November 2018. Accessed 20 February 2023.

- Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. Blood cannabinoids. I. Absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 1992;16(5):276-82. doi: 10.1093/jat/16.5.276 Published September 1992. Accessed March 2023.

Drug Interactions

- Kocis P, T, Vrana K, E: Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol Drug-Drug Interactions. Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids. 2020; 5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8489344/

- Thomas, T.F., Metaxas, E.S., Nguyen, T. et al. Case report: Medical cannabis—warfarin drug-drug interaction. Journal of Cannabis Research. 2022; 4 (6): https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-021-00112-x Published 10 January 2022. Accessed February 2023.

- Vaughn SE, Strawn JR, Poweleit EA, Sarangdhar M, Ramsey LB. The Impact of Marijuana on Antidepressant Treatment in Adolescents: Clinical and Pharmacologic Considerations. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(7):615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11070615

Smoking Cannabis and Lung Health Risks

- Kaplan A. Cannabis and Lung Health: Does the Bad Outweigh the Good? Pulmonary Therapy. 2021; 7(2):395-408. DOI: 1007/s41030-021-00171-8

- Hancox, R.J., Shin, H.H., Gray, A.R., Poulton, R., & Sears, M.R. Effects of quitting cannabis on respiratory symptoms. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46(1), 80–87. DOI: 1183/09031936.00228914

- Martinasek MP, McGrogan JB, Maysonet A. A systematic review of the respiratory effects of inhalational marijuana. Respiratory Care. 2016;61(11):1543-51. DOI: 4187/respcare.04846

- Polen MR, Sidney S, Tekawa IS, Sadler M, Friedman GD. Health care use by frequent marijuana smokers who do not smoke tobacco. Western Journal of Medicine. 1993;158(6):596-601. PMID: 8337854 PMCID: PMC1311782

Harm Reduction

- Canada’s Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines

- Fischer B, Jeffries V, Hall W, Room R, Goldner E, Rehm J. Lower Risk Cannabis use Guidelines for Canada (LRCUG): a narrative review of evidence and recommendations. Can J Public Health. 2011 Sep-Oct;102(5):324-7. DOI: 1007/BF03404169 Published Sept-Oct 2011. Accessed March 2023.

- Fischer B, Robinson T, Bullen C, Curran V, Jutras-Aswad D, Medina-Mora ME, Liccardo Pacula R, Rehm J, Room R, van den Brink W, Hall W. Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines (LRCUG) for reducing health harms from non-medical cannabis use: A comprehensive evidence and recommendations update. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2022; 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103381 Updated January 2022. Accessed February 2023.

Cited Sources & References

1) Veterans Health Administration. Evidence Synthesis Program. (2020). Cannabis Provider Education Packet. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/Cannabis-Provider-Education-Packet.pdf Published February 2020. Accessed 15 January 2023.

2) Health Canada. Consumer Information-Cannabis. 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/laws-regulations/regulations-support-cannabis-act/consumer-information.html. Published 14 June 2019. Accessed 13 February 2023.

3) Canadian Center of Substance Abuse and Addiction. 7 things you need to know about edible cannabis. 2019;1. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-06/CCSA-7-Things-About-Edible-Cannabis-2019-en.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed 10 March 2023.

4) Abrams DI, Vizoso HP, Shade SB, Jay C, Kelly ME, Benowitz NL. Vaporization as a smokeless cannabis delivery system: A pilot study. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2007;82(5):572–578. doi :1038/sj.clpt.6100200 Published Online 11 April 2007. Accessed 15 February 2023.

5) Jugl S, Sajdeya R, Morris EJ, Goodin AJ, Brown JD. Much Ado about Dosing: The Needs and Challenges of Defining a Standardized Cannabis Unit. Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids. 2021;4(2):121-124. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517154 Published: 17 June 2021. Accessed January 2023.

6) Fischer B, Robinson T, Bullen C, Curran V, Jutras-Aswad D, Medina-Mora ME, Liccardo Pacula R, Rehm J, Room R, van den Brink W, Hall W. Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines (LRCUG) for reducing health harms from non-medical cannabis use: A comprehensive evidence and recommendations update. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2022; 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103381 Updated January 2022. Accessed February 2023.

7) Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. Blood cannabinoids. I. Absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 1992;16(5):276-82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/16.5.276 Published September 1992. Accessed March 2023.

8) National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2017. https://doi.org/10.17226/24625

9) Newmeyer MN, Swortwood MJ, Barnes AJ, Abulseoud OA, Scheidweiler KB, Huestis MA. Free and Glucuronide Whole Blood Cannabinoids’ Pharmacokinetics after Controlled Smoked, Vaporized, and Oral Cannabis Administration in Frequent and Occasional Cannabis Users: Identification of Recent Cannabis Intake. Clinical Chemistry. 2016;62(12):1579-1592. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.263475 Published 10 October 2016. Accessed March 12, 2023.

10) Grotenhermen, F. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cannabinoids. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2003; 42, 327–360. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200342040-00003 Published 30 September 2003. Accessed 18 March 2023.

11) Adams IB, Martin BR. Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction. 1996 Nov;91(11):1585-614. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8972919/ Published November 1996. Accessed June 2023.

12) MacCallum CA, Russo EB. Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2018; 49:12-19. https://www.ejinme.com/article/S0953-6205(18)30004-9/fulltext Published March 2018. Accessed 12 March 2023.

13) Kramer JL. Medical marijuana for cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2014; 65 (2):109-122. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21260 Published 10 December 2014. Accessed 15 June 2023.

14) Gustavsen S, Søndergaard HB, Linnet K, Thomsen R, Rasmussen BS, Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F, Oturai AB. Safety and efficacy of low-dose medical cannabis oils in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2021; 48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2020.102708 Published February 2021. Accessed April 2023.

15) Lucas CJ, Galettis P, Schneider J. The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. British Pharmacological Society Journals. 2018; 84(11): 2477-2482. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13710 Published November 2018. Accessed 20 February 2023.

16) Zendulka O, Dovrtelova G, Noskova K, Turjap M, Sulcova A, Hanus L, et al. Cannabinoids and cytochrome P450 interactions. Current Drug Metabolism. 2016; 17 (3): 206–26. doi: 2174/1389200217666151210142051 Accessed 15 February 2023.

17) Stott C, White L, Wright S, Wilbraham D, Guy GA. Phase I, open-label, randomized, crossover study in three parallel groups to evaluate the effect of rifampicin, ketoconazole, and omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of THC/CBD oromucosal spray in healthy volunteers. 2. SpringerPlus; 2013. p. 236. doi: 1186/2193-1801-2-236 Published 24 May 2013. Accessed 15 June 2023.

18) Ujvary I, Hanus L. Human metabolites of cannabidiol: a review on their formation, biological activity, and relevance in therapy. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2016; 1:90–101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5576600/ Published April 2016. Accessed March 2023.

19) Thomas, T.F., Metaxas, E.S., Nguyen, T. et al. Case report: Medical cannabis—warfarin drug-drug interaction. Journal of Cannabis Research. 2022; 4 (6): https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-021-00112-x Published 10 January 2022. Accessed February 2023.

20) Antoniou T, Bodkin J, Ho JMW. Possible and actual interactions between cannabinoids and other medication. Drug interactions with cannabinoids. CMAJ 2020. doi: 1503/cmaj.191097 Published 2 March 2020. Accessed March 2023.

21) Brown J D, Rivera K J, Hernandez L Y C, Doenges M R, Auchey I, Pham T, & Goodin A J. Natural and Synthetic Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Uses, Adverse Drug Events, and Drug Interactions. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2021; 61(S2), S37S52. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.1871 Published 15 August 2021. Accessed June 2023.

22) Lopera V, Rodríguez A, & Amariles P. Clinical Relevance of Drug Interactions with Cannabis: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022;11(5), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11051154 Published 22 February 2022. Accessed March 2023.

23) Health Canada. Information for healthcare professionals: cannabis (marihuana, marijuana) and the cannabinoids: dried or fresh plant and oil for administration by ingestion or other means psychoactive agent. 2018. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/information-medical-practitioners/information-health-care-professionals-cannabis-cannabinoids-eng.pdf; 149-151. Published October 2018. Accessed 15 January 2023.

24) Bykov, K. CBD and other medications: Proceed with caution. Harvard Health Blog. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/cbd-and-other-medications-proceed-with-caution-2021011121743 Published 11 January 2021. Accessed April 2023.

25) Hsu, A., & Painter, N. A. (2020). Probable Interaction Between Warfarin and Inhaled and Oral Administration of Cannabis. Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 33(6), 915918. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190019854958 Published 18 July 2019. Accessed March 2023.

26) Pennsylvania State University, College of Medicine, Department of Pharmacology. (n.d.). NTI Meds to be Closely Monitored when Co-Administered with Cannabinoids. Published 30 April 2020. Retrieved from https://sites.psu.edu/cannabinoid

27) Kaplan A. Cannabis and Lung Health: Does the Bad Outweigh the Good? Pulmonary Therapy. 2021; 7(2):395-408. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41030-021-00171-8 Published December 2021. Accessed January 2023.

28) Hancox, R.J., Shin, H.H., Gray, A.R., Poulton, R., & Sears, M.R. Effects of quitting cannabis on respiratory symptoms. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46(1), 80–87. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/46/1/80 Published July 2015. Accessed January 2023.

29) Martinasek MP, McGrogan JB, Maysonet A. A systematic review of the respiratory effects of inhalational marijuana. Respiratory Care. 2016;61(11):1543-51. https://rc.rcjournal.com/content/61/11/1543 Published November 2016. Accessed February 2023.

30) Polen MR, Sidney S, Tekawa IS, Sadler M, Friedman GD. Health care use by frequent marijuana smokers who do not smoke tobacco. Western Journal of Medicine. 1993;158(6):596-601. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1311782/ Published June 1993. Accessed May 2023.

31) US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug fact sheet: vaping and marijuana concentrates. April 2020. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/Vaping%20and%20Marijuana%20Concentrates-2020.pdf

32) Ottawa Public Health. Lower risk cannabis use. https://www.ottawapublichealth.ca/en/public-health-topics/know-your-responsibility-.aspx. Published 2023. Accessed 10 June 2023.

33) Budney AJ, Sargent JD, Lee DC. Vaping cannabis (marijuana): parallel concerns to e-cigs? Addiction. 2015; 110(11):1699-704. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13036 Published 12 August 2015. Accessed 31 August 2023.

34) Tashkin DP. Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung. Annals of the American Thoracoracic Society. 2013;10(3):239-47. doi: 1513/AnnalsATS.201212-127FR Published June 2013. Accessed 15 January 2023.

35) Verhoeckx KC, Korthout HA, van Meeteren-Kreikamp AP, Ehlert KA, Wang M, van der Greef J, et al. Unheated Cannabis sativa extracts and its major compound THCacid have potential immuno-modulating properties not mediated by CB1 and CB2 receptor coupled pathways. Interational Immunopharmacology 2006; 6: 656–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2005.10.002 Published April 2006. Accessed March 2023.

36) Rock EM, Sticht MA, Parker LA. Effects of phytocannabinoids on nausea and vomiting. In: Pertwee RG, editor. Handbook of cannabis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2014: 435–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199662685.003.0023 Published August 2014. Accessed 27 June 2023.

37) Fischer B, Russell C, Sabioni P, van den Brink W, Le Foll B, Hall W, Rehm J, Room R, Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines: A Comprehensive Update of Evidence and Recommendations American Journal of Public Health. 2017; 107: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303818. Published 12 July 2017. Accessed March 2023.

38) Freeman T, Lorenzetti V. Using the standard THC unit to regulate THC content in legal cannabis markets. Addiction. 2023;118(6):1007-1009. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16183 Published 29 March 2023. Accessed 15 June 2023.

39) Government of Canada. Canadian cannabis survey 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/research-data/canadian-cannabis-survey-2022-summary.html#s1. Published December 16, 2022. Accessed January 14, 2023.

40) Cannabis NB. Edibles and Beverages. https://www.cannabis-nb.com/learn/cannabis-201/edibles–beverages/#:~:text=For%20all%20pre%2Dmade%20products,10%20mg%20when%20added%20up. Accessed 15 March 2023

41) Government of Canada. How to read and understand a cannabis product label: cannabis resource series. 2022; 7.https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/personal-use/how-read-understand-cannabis-product-label/how-read-understand-cannabis-product-label.pdf. Published July 2022. Accessed 5 March 2023.

42) Borodovsky JT, Crosier BS, Lee DC, Sargent JB, Budney AJ, Smoking, vaping, eating: Is legalization impacting the way people use cannabis? International Journal of Drug Policy. 2016; 35:141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.02.022 Published October 2016. Accessed March 2023.

43) Bailey JR, Cunny HR, Paule MG, Slikker W. Fetal disposition of delta 9- tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) during late pregnancy in the rhesus monkey. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1987. 90(2):315-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-008X(87)90338-3 Published 15 September 1987. Accessed 23 January 2023.

44) Brents Lk. Sex and Gender Health: Marijuana, the Endocannabinoid System and the Female Reproductive System. The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 2016; 89(2), 175–191. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4918871/. Published June 2016. Accessed February 2023.

45) Carsley, S., & Leece, P. Evidence brief: Health Effects of Cannabis Exposure in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding [PDF]. 2018. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/E/2018/eb-cannabis-pregnancy-breastfeeding.pdf Published November 2018. Accessed July 2023.

46) Center for Disease Control and Prevention. What You Need to Know About Marijuana Use and Pregnancy [PDF]. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/marijuana/factsheets/pdf/marijuanafactsheets-pregnancy-508compliant.pdf Published October 2021. Accessed March 2023.

47) Cook JL, & Blake JM. Cannabis: Implications for Pregnancy, Fetal Development and Longer-Term Health Outcomes [PDF]. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. 2018. https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/421/SOCI/Briefs/SocOfObsAndGynoCda_e.pdf Published May 2018. Accessed March 2023.

48) Fonseca BM, Rebelo I. Cannabis and Cannabinoids in Reproduction and Fertility: Where We Stand. Reproductive Sciences. 2022: 29, 2429–2439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-021-00588-1 Published 10 May 2021. Accessed 16 July 2023.

49) Garry A, Rigourd V, Amirouche A, Fauroux V, Aubry S, Serreau R. “Cannabis and breastfeeding.” Journal of Toxicology. 2009;596149. doi: 1155/2009/596149. Published 29 April 2009. Accessed 11 February 2023.

50) Government of Canada. Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? [PDF]. 2018. https://www.cpha.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/resources/cannabis/evidence-brief-pregnancy-e.pdf Published August 2018. Accessed March 2023.

51) Grant KS, Petroff R, Isoherranen N, Stella N, Burbacher TM. Cannabis Use During Pregnancy: Pharmacokinetics and Effects on Child Development. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2018; 182, 133–151.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.08.014 Published February 2018. Accessed March 2023.

52) Gundersen TD, Jørgensen N, Andersson A-M, et al. Association between use of marijuana and male reproductive hormones and semen quality: A study among 1,215 healthy young men. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2015; 182(6): 473-481. doi: 1093/aje/kwv135 Published 15 September 2015. Accessed 13 March, 2023.

53) Gunn JK, Rosales CB, Center KE, Nunez A, Gibson SJ, Christ C, and Ehiri, JE. Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 6. 2016:4: e009986. doi: 1136/bmjopen-2015-009986. Accessed May 2023.

54) Herrmann, ES, Cone EJ, Mitchell JM, Bigelow GE, LoDico C, Flegel R, and Vandrey R. Non-smoker exposure to secondhand cannabis smoke II: Effect of room ventilation on the physiological, subjective, and behavioral/cognitive effects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2015; 151:194-202. doi: 1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.019 Published Online April 5, 2016. Accessed January 20 2023.

55) Hutchings, DE, Martin BR, Gamagaris Z, Miller N, and Fico T. Plasma concentrations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in dams and fetuses following acute or multiple prenatal dosing in rats. Life Sciences. 1989; 44 (11):697-701. doi: 1016/0024-3205(89)90380-9. Accessed February 2023.

56) Leech SL, Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, and Day NL. Prenatal substance exposure: effects on attention and impulsivity of 6-year-olds. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 1999; 21 (2):109-18. doi: 1016/s0892-0362(98)00042-7. Published March 1999. Accessed February 2023.

57) MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. The Effects of Marijuana on Embryo Development. 2017. https://womensmentalhealth.org/posts/effects-marijuana-embryo-development/. Published April 2017. Accessed March 2023.

58) Moore C, Coulter C, Uges D, Tuyay J, van der Linde S, van Leeuwen A, Garnier M, and Orbita J. Cannabinoids in oral fluid following passive exposure to marijuana smoke. Forensic Science International. 2011; 212 (1-3):227-30. doi: 1016/j.forsciint.2011.06.019 Published 10 October 2011. Accessed 13 March 2023.

59) Perez-Reyes M, and Wall ME. Presence of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in human milk. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1982; 307 (13):819-20. doi: 1056/nejm198209233071311 . Published 23 September 1982. Accessed March 27 2023.

60) Pizzol D, Demurtas J, Stubbs B, Soysal P, Mason C, Isik AT, Solmi M, Smith L, Veronese N. Relationship Between Cannabis Use and Erectile Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2019 ;13(6):1557988319892464. doi: 1177/1557988319892464 .Published Nov-Dec 2019. Accessed June 2023.

61) Reece-Stremtan S, and Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeeding Medicine 2015;10 (3):135-41. doi:1089/bfm.2015.9992 Published 1 April 2015. Accessed 15 June 2023.

62) Sharma P, Murthy P, Bharath MM. Chemistry, metabolism, and toxicology of cannabis: clinical implications. Iran J Psychiatry. 2012;7(4):149-56. PMCID: PMC3570572 Published Fall 2012. Accessed March 2023.

63) Statistics Canada. National Cannabis Survey, second quarter 2019 [PDF]. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/190815/dq190815a-eng.pdf?st=aX9_MCSh Published 15 August 2019. Accessed February 2023.

64) Wu CS, Jew CP, Lu HC. Lasting impacts of prenatal cannabis exposure and the role of endogenous cannabinoids in the developing brain. Future Neurology. 2011 Jul 1;6(4):459-480. https://doi.org/10.2217/fnl.11.27. Published 5 January 2012. Accessed April 2023.

65) Pacey A, Povey A, Clyma J-A, et al. Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for poor sperm morphology. Human Reproduction. 2014; 29(8): 1629-1636. doi: 1093/humrep/deu116. Published August 2014. Accessed July 2023.

NB Lung has been helping New Brunswickers breathe easier since 1933.

Thank you for your support!

Page Last Updated: 28/02/2023